Death, Taxes, And An Unexpected Windfall

Edward H. Harriman’s Estate and the Building of the Utah State Capitol

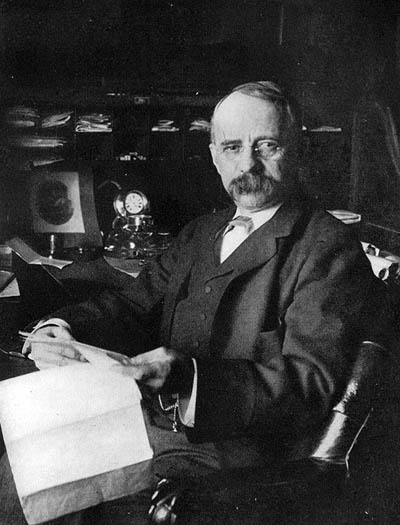

Edward “Ned” Harriman, circa 1907

A NEW YORK CAPTAIN OF INDUSTRY COMES TO UTAH

Late 19th-century America saw rapid technological change and industrial advances, which in turn made a relatively small group of Americans massively wealthy. Among the newly-minted rich was Edward H. “Ned” Harriman, a New York stockbroker who specialized in rebuilding railroads.

In 1897, the U.S. government foreclosed on the bankrupt Union Pacific Railway. Because of the railroad’s importance to the economy, the government sold the railway at a discount and allowed a group of investors, led by Harriman, to reorganize as a new corporation. Harriman and his group incorporated the new railroad in Utah to take advantage of the state’s favorable business environment and low taxes. After forming the Utah-based Union Pacific Railroad, Harriman invested heavily in long-needed improvements and reaped large dividends as the railway flourished.

ENFORCING Utah’s Inheritance Tax Law

Utah’s capitol story is linked with Utah’s long-delayed quest for statehood. The state’s early Euro-American settlers first petitioned for statehood in 1849. After half a dozen subsequent attempts, Congress passed an enabling act in 1894, starting a process that ended on January 4, 1896. Utah became a state 49 years years after its first petition. The Utah State Capitol was completed in 1916.

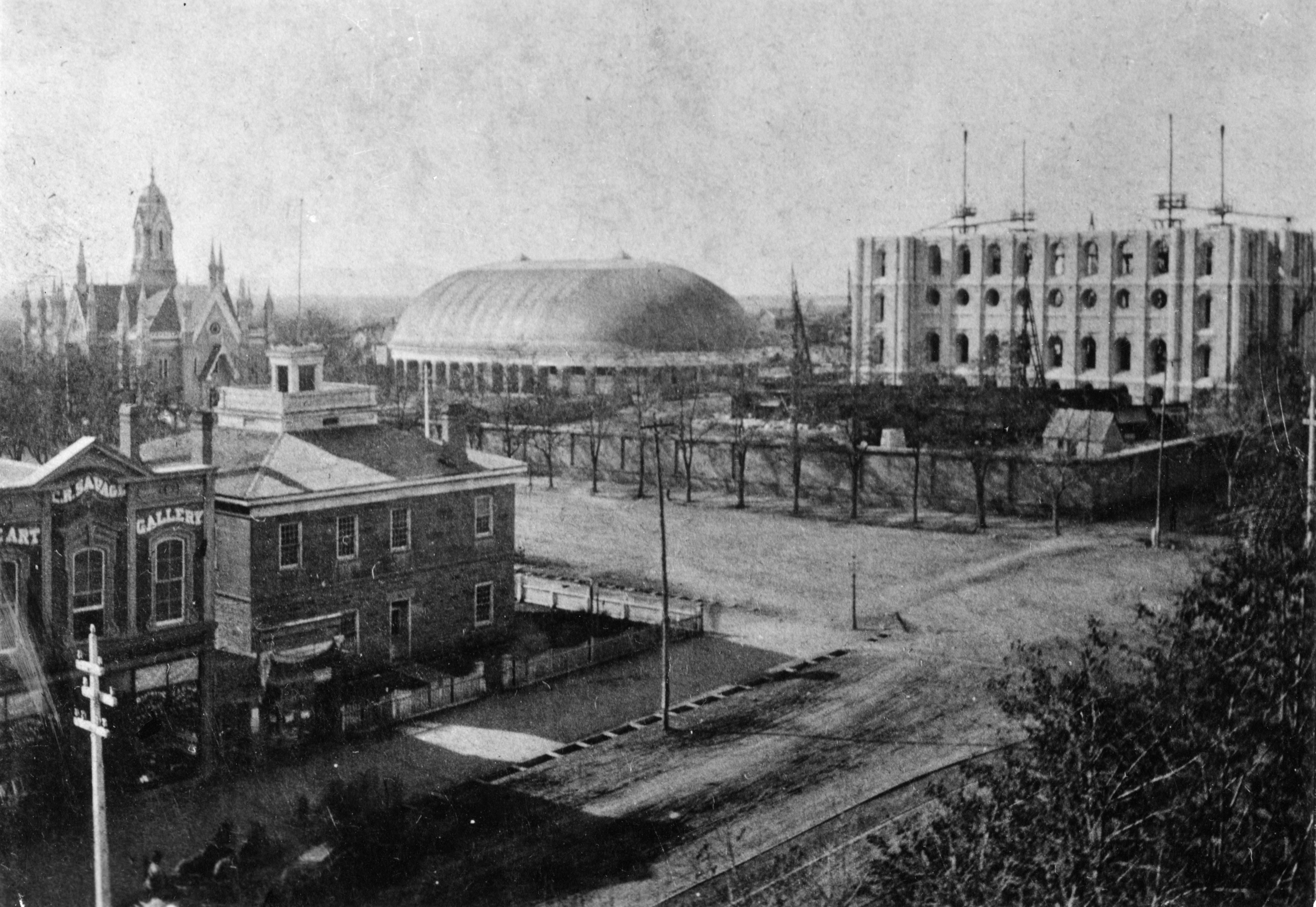

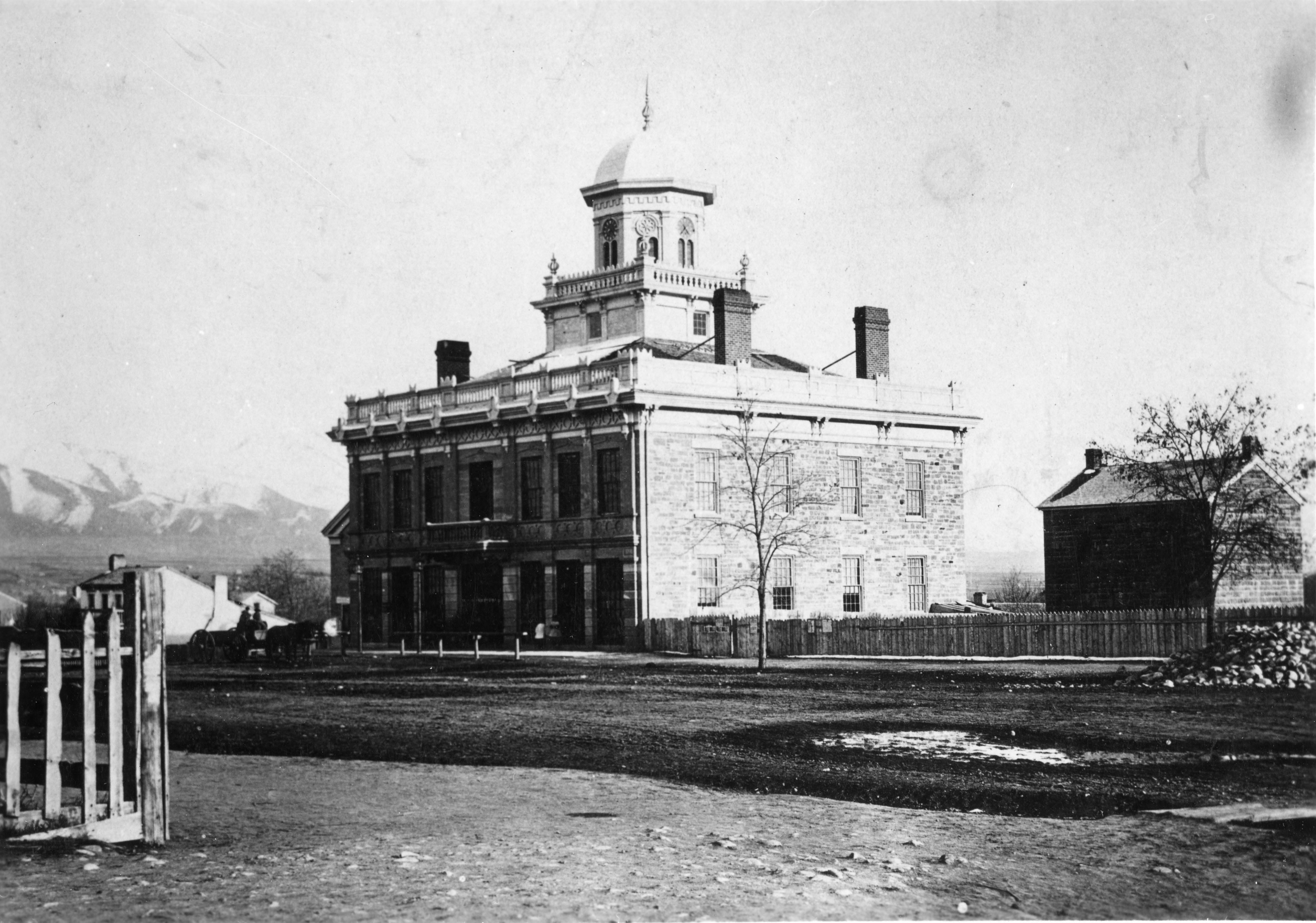

Like its unresolved statehood petitions, Utah’s statehouse moved “from pillar to post” for 67 years. These included the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Council House, an intentionally-built Utah Territorial Capitol located in Fillmore, Salt Lake City Hall, and the Salt Lake City & County Building. The latter served as territorial and state capitol until Utah’s current capitol was completed in 1915-1916.

When the Harriman estate reported in December 1910 that the tax would be paid, Governor William Spry and Republican Party leaders started discussing the use of this financial windfall for a capitol building. During the last two days of the 1911 Utah Legislature, the Harriman funds served as catalyst for the passing of five bills (including the remaining funding) so Utah would finally get its State Capitol.

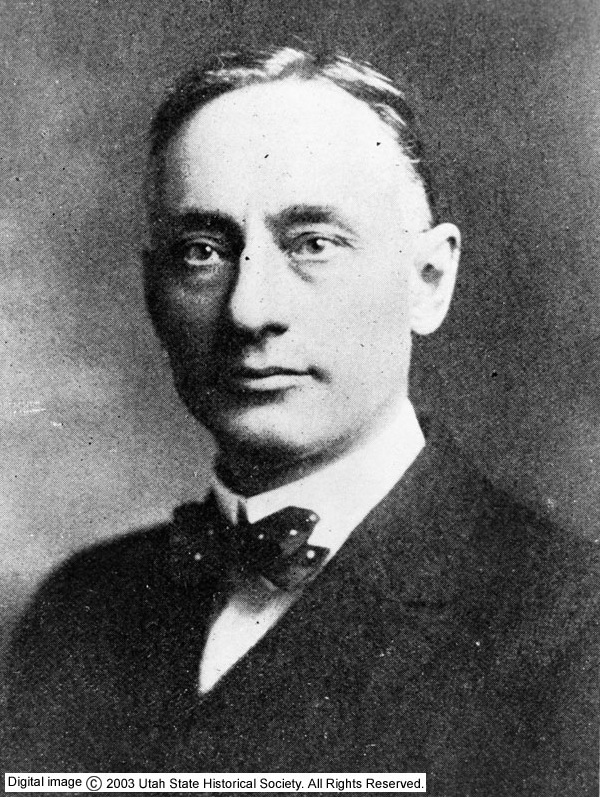

Albert R. Barnes, Utah’s Attorney General 1909-1917

An unexpected windfall funds the Utah State Capitol

Harriman’s death in 1909 came during the national Progressive Movement (1890-1920), a reaction to the country’s dismal public health conditions, rampant political and corporate corruption, and deepening economic chasm between the very rich and the struggling majority middle class.

Utah’s 1901 Inheritance Tax was a product of this movement. As Utah Attorney General Albert R. Barnes reviewed the results of the tax, he noticed a lack of enforcement for non-resident estates holding stocks issued by companies incorporated in Utah. Barnes learned New York state had received inheritance tax from Harriman’s estate for stocks held in New York companies. He reasoned Harriman’s stock in the Union Pacific, incorporated in Utah, should be subject to Utah’s Inheritance Tax law. For a year, Barnes pressed Harriman’s estate to comply with the law. Finally, on March 6, 1911, Harriman’s estate issued a check to the State of Utah for $798,536.85, or five percent of the Union Pacific’s estimated stock value of more than $15 million.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Council House 1849-1883

Utah Territorial Capitol in Fillmore 1855-57

Salt Lake City Hall 1866-1894

Salt Lake City & County Building 1894-1916

Fighting Teddy

Harriman, renowned as one of America’s corporate giants, became a target for President Theodore Roosevelt’s “trust busting.” Under the Sherman Act (1890) and the Hepburn Act (1906), created to protect consumers from monopolies, President Roosevelt sued more than 40 U.S. corporations. Those anti-monopoly targets included the Union Pacific, which under Harriman’s direction had purchased a majority interest in nearly every major western and Midwest railway.

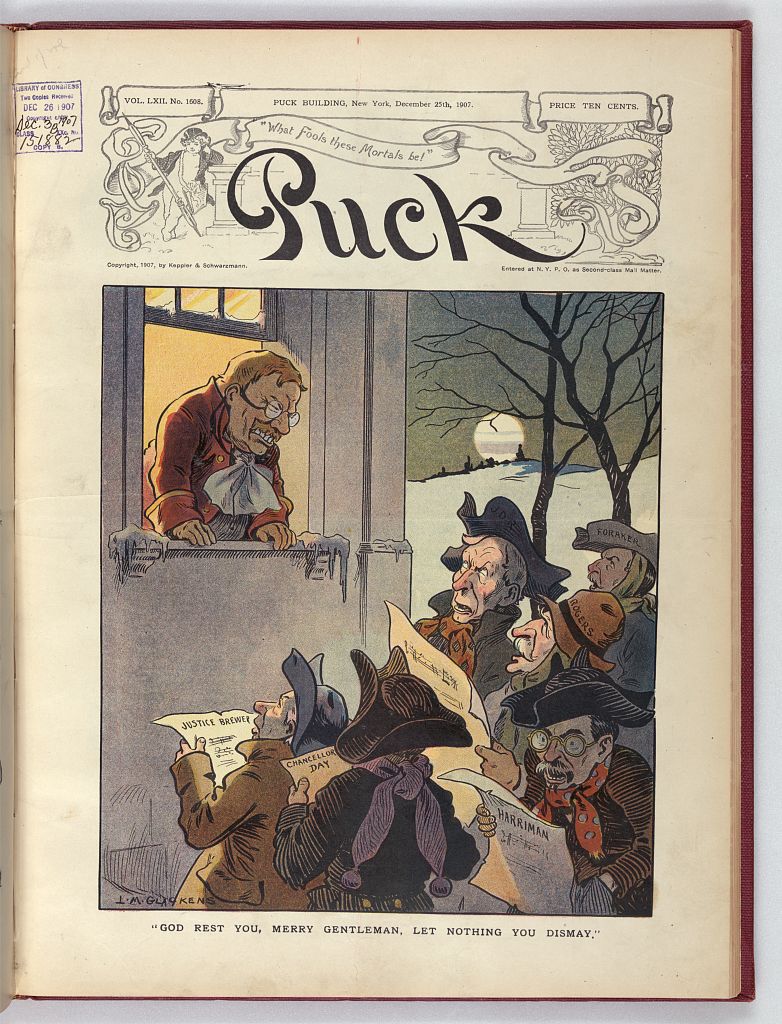

Cartoonists in national publications mocked the corporate titans, including Harriman. The cartoon on the left, for example, shows Harriman and others pleading in song to President Roosevelt to “rest” and not break-up their expanding corporations.

Chasing Butch

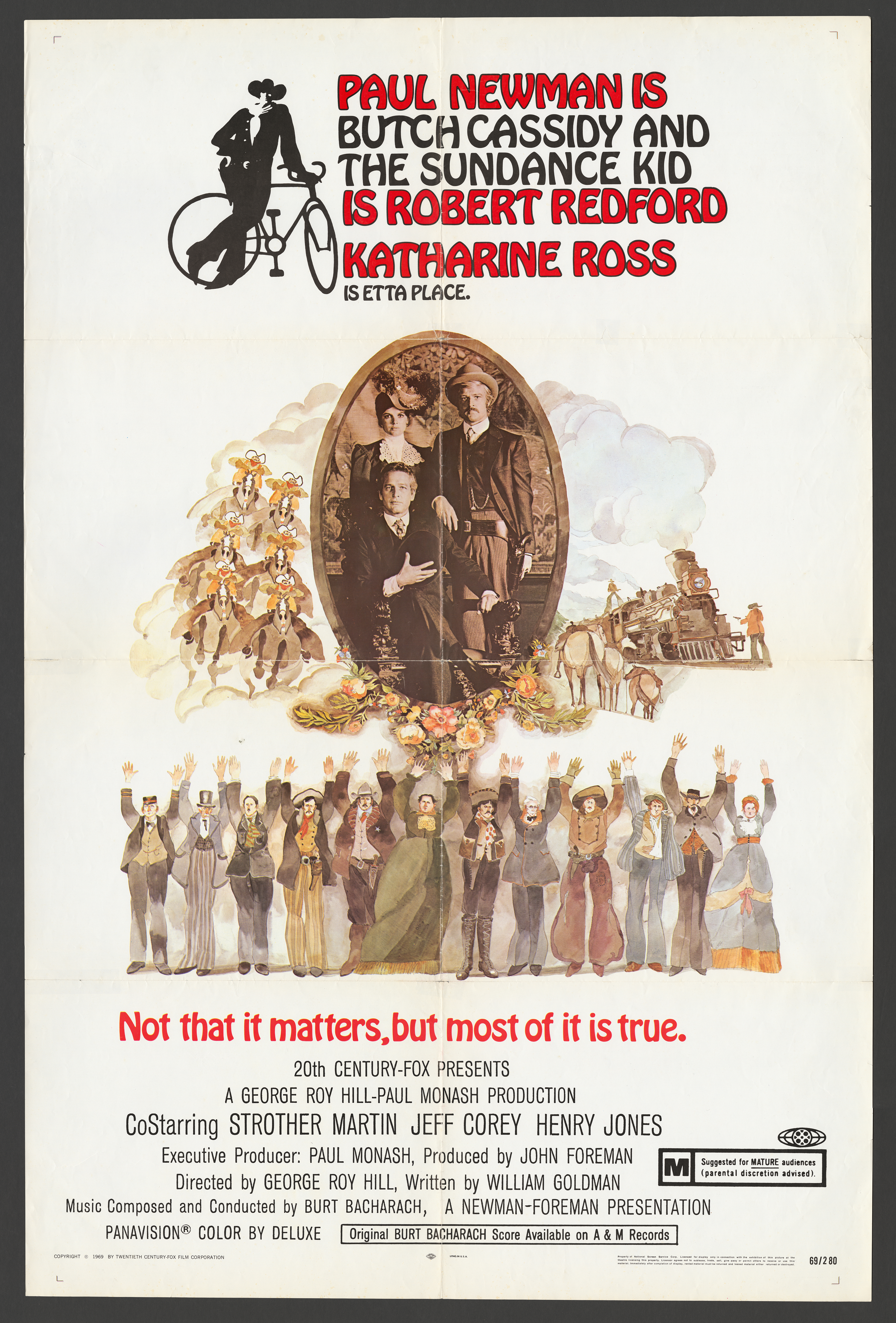

As Chairman of the Board and President of the Union Pacific Railroad, Harriman arranged for his Union Pacific Security Services to track down Utah’s Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid, and the rest of the Wild Bunch, who were robbing Union Pacific trains in the early 1900s.

In the 1969 film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Butch (Paul Newman) talks with a real-life Union Pacific clerk named Woodcock, who tries to stop the train robbery by evoking Harriman’s name. The dialogue underscores just how well-known Harriman was in the early 20th century, and how perfectly suited he was as an establishment foil for the 1960s counterculture characters who were “sticking it to the man!”

Curated By Brad Westwood, Public Historian