How does a hip youth arts agency stay digitally relevant as it enters its third decade?

By Ellen Fagg Weist | Photography by Keith Johnson

In the grand tradition of indie bands, Sincerely, The Universe found inspiration for its name from graffiti scribbled on a bathroom stall.

The name suited a band of musicians thrown together in Spy Hop’s after-school music class. “Six strangers who became best friends while writing music,” is how 18-year-old guitarist Hannah Williams describes them. Performing their songs at a Red Butte Garden concert in July was the musicians’ opportunity to send their own message to the universe of what it means to be young and alive right now.

After months of writing and recording, the band performed original songs grappling with real-life issues, such as “Try,” a challenge to a generation so caught up in pretty social media pictures that they forget to live.

Playing in the band changed everything about her ability to communicate about sound, says Williams, after two years of studying music production at Spy Hop. She has joined two other bands, and she hopes to open an all-ages recording studio someday.

Now that Williams has graduated from high school, she plans to stick around Spy Hop working as a peer mentor. She’s devoted to the agency for the way it helps students see what’s happening in the world, and then holds them responsible to make things better. “I don’t think I’ll ever fully leave,” Williams says, even as she acknowledges: “Everything I have learned there has helped me prepare for life outside of it.”

For 20 years, Spy Hop has provided the technology and training for Utah youth to express themselves. Now the youth arts agency is writing the next chapter in its own coming-of-age story.

“The joke is: Spy Hop is too old to go to Spy Hop classes.”

—Adam sherlock, director of community partnerships & learning design

Spy Hop’s maturity was in evidence in August at the groundbreaking for a new $10 million, 22,000-square-foot center in Salt Lake City’s Central Ninth district. The new building, scheduled to open next year, was strategically placed at the intersection of the valley’s three TRAX lines, in hopes of providing accessibility to kids without cars or who might be too young to drive.

The building represents a beacon of stability, a tangible investment for the program founded on the idea of amplifying youth voices. “We’ll be legitimized by what the space is,” Sherlock says. “Because we’re not attached to a school, we’re something unique. We want kids to say: ‘That’s going to be my place.’”

Twenty years ago? Remember 1999? That was before a Google search sent targeted ads, before Alexa eavesdropped on conversations, before Facebook began storing photos in facial recognition databases. That was before people began using phones to make films about their lives. That was before kids grew up as digital natives.

“Unless people stop having babies, unless we no longer have teenagers, unless we’re no longer humans trying to connect with each other, there’s a need for Spy Hop,” says Kasandra VerBrugghen, executive director.

“This work becomes more and more relevant as we become more and more complex as a society.”

— Kasandra VerBrugghen, SPY HOP executive director

“You can share stories of your triumphs, struggles,” Gabriella Huggins tells kids in this “Sending Messages” podcast workshop. “Each of you is going to make an audio piece, and I will craft those pieces into an episode.”

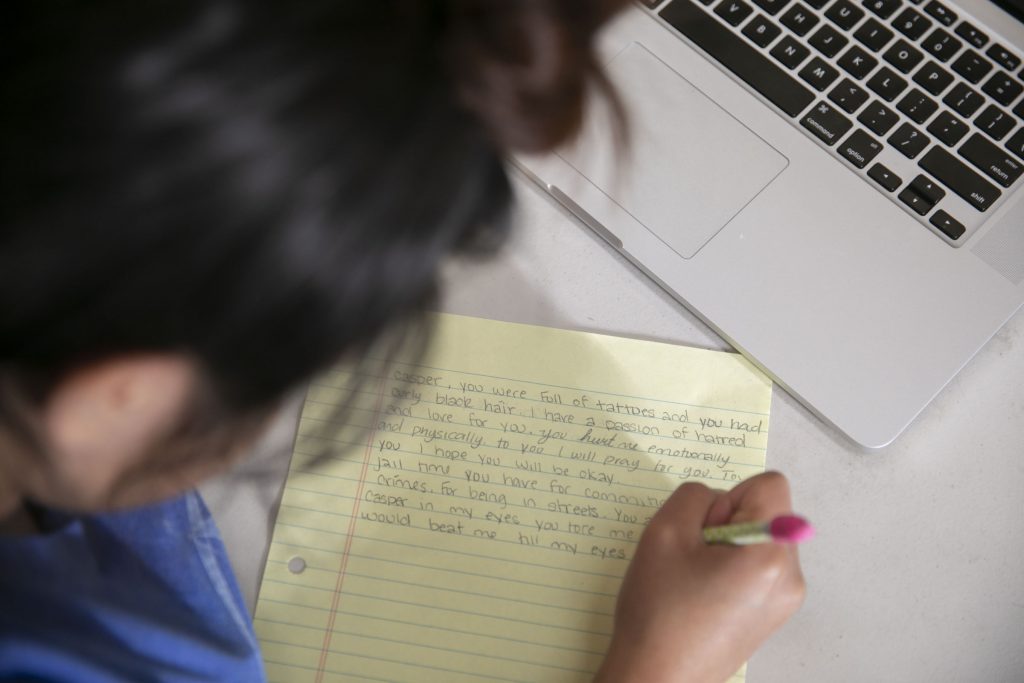

Six teens are clustered around laptops in a plain cinderblock room that doubles as a lunchroom at Odyssey House’s Teen Inpatient Center, a downtown Salt Lake City addiction treatment program. Huggins asks each student to select a pseudonym.

Nationally, “Sending Messages” is the only ongoing podcast recorded inside youth-in-care facilities. Locally, it’s an example of the breadth of Spy Hop’s programs.

The first step for this workshop is choosing a theme for the episode. “Hope” is one suggestion. “A good broad topic, but maybe a little too broad,” Huggins says. “But I do think hope is important.”

Other suggestions: “Then and now.” “Survival strategies.” “Rites of passage.” “Family.” “Inspiration.” “Passion.” “Pathways.” “Courage.” “Spirituality.” “Relationships” earns the most votes.

Use any format you want, Huggins says. Prose. Rhyming prose. Stream-of-consciousness. Letters. “Any form that makes sense to you, that feels good to you,” she says. “We’re going to give you 20 minutes to write. Cool?”

Huggins, 25, is a West High graduate who created an award-winning documentary at Spy Hop where she attended classes there until she aged out at 19. She worked odd jobs for a while, then returned as the community programs mentor four years ago.

“Kids all like the tools. Writing is everybody’s least favorite part.”

— Gabriella Huggins, spy hop Community programs mentor

One girl, Nikki, worries about the sound of her voice. “When I hear my voice on the recorder, I sound like a man,” she says.

“The question is: How is your voice working stylistically?” Huggins answers. As a mentor, she’s no-nonsense and efficient, her manner reinforcing Spy Hop’s Code of Content, which challenges kids to think about what they’re adding to the conversation rather than just making noise.

Like every other nonprofit, Spy Hop has a founding story: It was launched in 1999 by two guys with great timing who didn’t really know what they were doing.

Tutors Rick Wray and Erik Dodd were looking for a learning project that would get teenagers excited. Drawing upon their own filmmaking experience, they signed up 12 kids to make a documentary about the possibilities of a new millennium. Remarkably, they ended the year with the same crew, and their 30-minute documentary, “The Hourglass Project,” aired on HBO.

The founders took that distinctive name, Spy Hop, from a verb describing the moment when a dolphin or whale peeks out of the water to see what’s ahead.

The fledgling after-school program was at first based in a gritty office with a leaky ceiling. New staffers were directed to buy their own desks at Deseret Industries.

Founders quickly learned to put professional equipment in kids’ hands right away, but their core strategy was even more ambitious. “What’s unique is the idea of youth media as a movement, of using digital media — radio, film and music — to tell stories and impact change,” says Larissa Trout, director of marketing and community relations.

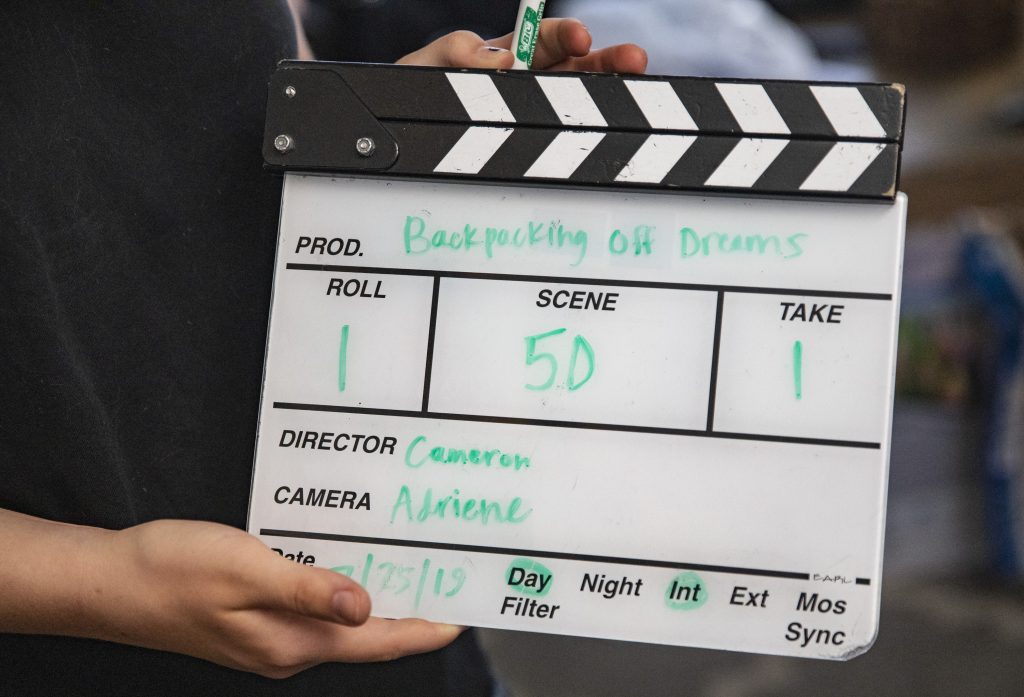

Along the way, the scrappy agency added music, audio, and video game training to its filmmaking programs. In 2008, Spy Hop launched a student-run record label, now known as 801 Sessions, and later the “Sending Messages” podcast. The Resonate music class helps kids learn to write hip-hop lyrics and beats, while the Musicology class assembles musicians into a band, like Sincerely, The Universe, and helps them record a professionally produced album. More recently, Spy Hop launched media training programs at high schools and communities around the state.

“Every time I see a new face walk in the door, I’m kind of mystified. The 16-year-old me would never have had the guts to do that.”

— ADAM SHERLOCK

It’s easy to assume, mistakenly, that Spy Hop only appeals to hip kids. Kids with tattoos. Kids with an attitude. Or rich kids.

But staffers say they work hard at “finding the kids who are harder to find,” Trout says. Most classes and workshops are free. Adds Sherlock: “We think so deeply, work so hard, to try to find the kids who think it’s not for them.”

Most Spy Hop students don’t go on to film or game design or music schools, but that’s not the aim. “We teach the intrinsic worth of art in the form of ‘future-ready skills,’” Sherlock says. “When you make something, you learn something.”

“At Spy Hop, these kids become a family,” says Jean Tokuda Irwin, arts program manager at Utah Arts & Museums and a Spy Hop advisory board member who has helped nurture the agency from its inception.

“The wealthy kids become friends and colleagues and co-creators and co-dreamers and storytellers with the kids from the other side of the tracks.”

— Jean Tokuda IRWIN, Utah Department of Heritage & Arts

Another day, the first morning of “Honey, I Shrunk the Spy Hop Kids,” a weeklong summer camp focusing on digital design. Mentor Elizabeth Schulte is teaching beginning Photoshop to 11 preteen campers. “We don’t need to worry about exact right now,” she says. “We’re doing something quick, cool and fast.”

Schulte explains her teaching method this way: “I take a really big concept and distill it down to what gives these kids success the fastest. Rinse and repeat.” In class, she announces an assignment and then sets a quick time limit on her phone, “because I’m a video game designer. I gamify everything.”

“I need extreme help,” one boy says.

“I can provide help in an extreme fashion,” Schulte responds, kindly. Her colleagues call her Santa Claus for Nerds, because of her vast storehouse of pop culture knowledge.

“I’m delivering magical powers to you guys,” says Schulte with enthusiasm as she explains how Command-Z undoes the last step. In Schulte’s words: “Command-Z lets you step back in time.”

A few years ago, Schulte was a painter studying fine art at Utah Valley University. After she learned about Command-Z in a digital media class, she applied the idea to her oil painting. It helped her shed her fear about making a mistake on her next brushstroke.

That completely changed her creative life, which is why she’s so quick to help her young charges overcome perfectionism.

“It’s very important to teach artists their work is disposable.”

— Elizabeth schulte, spy hop design mentor

The agency’s website defines the “Spy Hop special sauce” this way: “One part education, two parts media and three parts empowerment.” Around the offices, there’s the cliché of the “Spy Hop push,” that moment when a student is challenged to ambitiously look ahead — like a dolphin or a whale — and then refocus on editing her work one, or six, more times.

Seven current staffers are Spy Hop alumni, five have their own children enrolled, and a handful of former mentors are now program directors. Since much of the staff have grown up professionally together, that longevity means “the Spy Hop way” is baked into the agency’s DNA.

What’s unusual about Spy Hop is that it offers the kinds of digital media classes usually found in larger urban areas. Then there’s the sophisticated, award-winning artistic quality of the work students create, says Mindy Faber, a consultant who heads the Convergence Design Lab at Chicago’s Columbia College and has been studying Spy Hop almost from its beginning.

One of Spy Hop’s successes has been developing showcases for student work, from events such as the Heatwave Music Festival to the PitchNic and Reel Stories film premieres. Audio kids, who call themselves Loudies, host Saturday night’s “Loud & Clear Youth Radio Hour” on KRCL.

In the annual PowerUp! Game Design Lab, students are challenged to create a socially conscious video game. This year’s Tetris-based game, “Downpour,” debuted at the Urban Arts Gallery for July’s gallery stroll. The game focuses on confronting depression, a particularly relevant issue in a state facing an exploding youth suicide crisis.

“The blocks represent life’s pressures and how you handle it,” says Quentin Blanchard, 15, an East High student who wrote the game’s text.

“It’s really cool to see people play the game,” says Connor Watson, 15, who attends the Academy of Math, Engineering and Science at Cottonwood High. He led coding for the game and worked on the game’s logic problems. “People play it in different ways.”

This year’s Heatwave Music Festival seemed aptly named, as temperatures hung above 100 degrees on a sweltering July night.

More than 400 people attended the Monday night showcase, the largest crowd ever. Young kids threw Frisbees and raced around, while grownups lounged on the lawn. Parents filmed videos on their phones while teenagers performed radio monologues and hip-hop and rock songs, during a concert hosted by Loudies.

Photographs by Amber Dwyer for Spy Hop

Sincerely, The Universe took the stage as the evening was finally cooling down to play a 12-song set from their newly released album, “Same Color Purple.” Two younger sisters rushed the stage to hoist hand-lettered fan posters.

The band was assembled last October after auditions led by music mentor Cathy Foy, a noted local drummer. The band had written songs and rehearsed together for 10 months, playing professional gigs at Kilby Court and the Utah Arts Festival.

Tonight, though, playing on one of the state’s most beautiful stages, singer Gwen McConkie was emotional. “Ms. Cathy Foy, I love you so much,” she called from the stage. “We’re all best friends now because of what Spy Hop has done for us.”

Attend a handful of events and classes, and it’s easy to consider Spy Hop a youth arts production factory, but that misses the point. In a red state like Utah, kids across ethnic and religious and economic cultures say they feel at home. Students tell researchers they feel accepted and challenged, while they are encouraged to express themselves authentically.

“There’s way more going on at Spy Hop than learning how to use technology to make media,” says Faber, the consultant, who marvels at how articulate Utah students are at explaining why they’ve made a home at the nonprofit. “They’re making good human beings.”

BY THE NUMBERS: SPY HOP COMES OF AGE

Agency: Founded in 1999

Annual budget breakdown: $1.7 million; 27 percent donated from foundations; 8 percent from corporations; 7 percent from individuals; 38 percent from government funding; and 20 percent from earned income.

Staff: 23

Prestige: At a White House ceremony in 2015, Spy Hop was one of 12 programs recognized with a National Arts and Humanities Youth Program Award, from a pool of 285 nominees.

Annually serves: 15,000 students statewide

After-school programs: 1,000 students

New building: $10 million, 22,000 square-feet over three stories, scheduled to be completed in late summer 2020.

Address: 208 W. 900 South, Salt Lake City

Includes: Soundstage for film production with prop storage; recording studio, with two vocal booths and control room; electronic music lab for beatmaking; media lab with classrooms and editing bays; student lounge; and rooftop event space.

WEBSITE: spyhop.org

NEXT EVENT: PitchNic, a premiere of four short films written, directed and produced by Utah teens, about emotional abuse, immigration, chronic illness and coming of age. November 2019, at Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center, 138 W. Broadway, Salt Lake City. 7:30 p.m.

Read Other MUSE Stories: