Salt Lake West Side Stories: Post Fourteen

by Brad Westwood

It is no surprise that in terms of public health, sanitary reform, and civic improvements, local and state leaders neglected Salt Lake City’s ethnically diverse and industrial west side.

The west side sits along the floodplain of the Jordan River and the southern end of City Creek’s alluvial deposit. At the same time, the city’s surrounding topography radiates upward to the north and east. The rest of Salt Lake City and its earliest suburbs were built on tablelands and foothills. In 1849, James E. Squire described the topography of the Salt Lake Valley in a letter to a friend. You may return to Post 6 to read this quote starting with “My Dear Friend…“. From its onset, Salt Lake’s west side has been fighting against something of a topological disadvantage.

During Salt Lake City’s pioneer and territorial periods (1847-1896), residents and officials channeled City Creek and other canyon stream water into miles of ditches for irrigation and domestic use. Then in the early 1880s, Salt Lakers built the Jordan Canal to draw water from Utah Lake. The Jordan Canal ran along the west side of the Jordan River to North Temple and Main Street, and then flowed southward across the city. All of the unused or spent water finally drained into larger canals that ran through the Pioneer Park neighborhood. These larger canals poured into the Jordan River until it reached the Great Salt Lake. Groundwater also flowed below ground through layers of alluvial rock and gravel to the Jordan River.

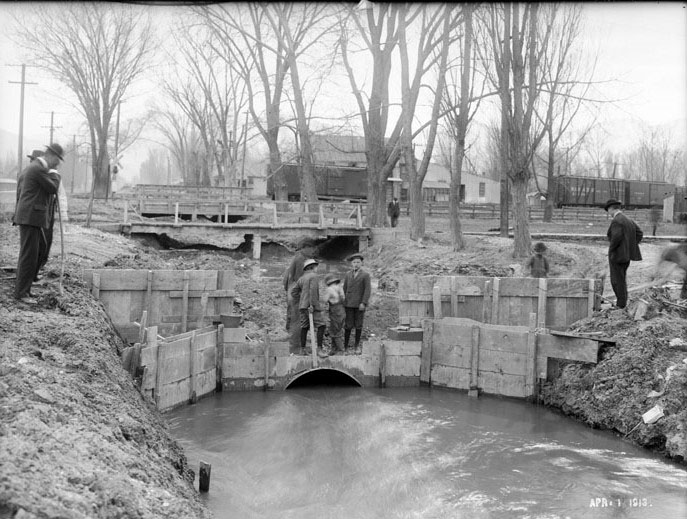

Water was not the only substance that moved through the Pioneer Park neighborhood. Before the building of municipal sewage systems, the city built large open canals to reduce spring flooding. One channel ran down 600 South. Another carried runoff from the north along 900 South and followed 400 West to 100 West. Over time these canals became open sewers that were filled with storm drainage, industrial drainage, and human and animal excrement. Before gas-powered vehicles and mechanized farm equipment, horses, oxen, mules, and donkeys pushed and pulled wagons, carriages, and equipment throughout the city streets. They dropped their waste as they worked. Sewage from shallow or overflowing outhouses and private septic pits also tainted the area’s soil and water. Consequently, the neighborhood had disproportionately high numbers of recorded waterborne illnesses. Because of the west side’s heavy industries and because of its multiple train depots, the neighborhood had more than its share of industrial, human, and animal waste.

“Water was not the only substance that moved through the Pioneer Park neighborhood.”

Beginning in 1893, city planners designed a municipal sewage system hoping to resolve the city’s waste problems. The sewer system consisted of a number of brick-lined pipes that ran along Main Street until turning west on 500 South to carry the contents to the Jordan River Surplus Canal. The waste flowed in the canal until it was dumped into the Great Salt Lake. Unfortunately, more affluent parts of the city, the commercial center, and newly established suburban neighborhoods, all received the municipal sewage system before the gritty, industrial and international west side did. As historian Ben Carter argues, city officials ignored or purposely delayed any health or civil improvements to the Pioneer Park neighborhood. In short, the poverty and the diversity of the west side made it the last priority of city officials seeking to clean up Salt Lake City’s streets.

In addition to inadequate sewage drainage and systems, compared to more affluent neighborhoods, Pioneer Park neighborhood residents had less indoor plumbing, many lacked piped water to sinks, baths, or showers. Without municipal sewers (and even after the systems were installed) outhouses remained in use longer than in other areas of the city. However, newer and more expensive apartment buildings did offer what they coined as “modern conveniences” that included separate furnaces and bathrooms located down the hall from the rooms. Local landlords often preferred renting to white people and charged people of color more. Between the city’s water runoff making its way to the Jordan River, along with miles and miles of railroad tracks, and a preponderance of unpaved roads, the west side contributed to Salt Lake’s reputation as one of the United States’ dirtiest cities.

Public health problems continued to plague west side residents well into the twentieth century. Like other parts of the United States, race influenced social status in Salt Lake City. In Utah, affluent white members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter LDS Church, also known as Mormons) sat at the top of the social hierarchy. As a result, they had access to improved municipal infrastructure first, while people of color and impoverished white people suffered the most environmental consequences of industrialization and urbanization. Most often, living status also reflected a broader inability to fully participate or obtain community political and decision-making power. Other than landowners and corporations, the west side had little political clout.

While improvements to the Pioneer Park neighborhood were slow, the city did fund projects to change the physical space and the reputation of the area. One such change took place at the site of the Old Pioneer Fort. For years, locals called the ten-acre block – which was the only remaining identified section of the settlers 44-acre fort – the “Old Fort Square” or “Pioneer Square.” In prior decades, landowners (the LDS Church and then Salt Lake City) either tolerated squatters or rented portions of the block for farming or gardening. Several times during the 1890s, Pioneer Park was nearly sold to railroads interested in building a train depot and a railroad yard. These railroad companies and their city supporters argued that transforming this unused, open urban space, into an industrial yard and depot would be for much “public good.” Despite constant calls and inquiries for the block to be put to “better” use, the park somehow remained an open piece of land in an otherwise growing industrialized and urban city.

Pioneer Park had more than one owner. The LDS Church were the original owners of the block. The church sold it to the city in 1883. Shortly after the finalization of the purchase, city leaders held a design competition for landscaping the city’s four parks: Liberty Park, Washington Square, Tenth Ward Square, and Pioneer Park. William J. Jones won a ten-dollar premium for his design of the future Pioneer Park. It appears Jones’ plan was never executed. In fact, the city waited again to turn the fallow fields into a park until 1897, when Utah and Salt Lake City celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the arrival of Mormon pioneers to the Salt Lake Valley. In commemoration, the city dedicated the pioneer fort block to be hereafter the “Salt Lake City Pioneer Park.” It was not fully landscaped and opened to the public until 1903.

Salt Lake’s west side was most often the last neighborhood to receive public health and infrastructure improvements. However, because of dedicated Progressive Era planners and concerned citizens, as well as renewed commitment from the LDS Church and city leaders to preserve the first settlement location, the neighborhood eventually lost its “dirtiest city” label.

We hope you join us for our next installment of Salt Lake West Side Stories where we will address the city’s efforts to re-direct prostitution from the city center to the west side, and how planners designed and constructed the Pioneer Park.

Do you want to read the next post (Post 15)? THE PROGRESSIVE ERA, THE MAKING OF A PROPER PARK, AND THE “STOCKADES”

Click here to return to the complete list of posts.

Contributors: This post was researched and written by Brad Westwood with a whole lot of help from friends. Thanks to our sound engineer and recording engineer Jason T. Powers, and to his supervisor Lisa Nelson, both at the Utah State Library’s Reading for the Blind program. Thanks also to yours truly, David Toranto, for narrating this post.

Selected Readings:

“Letter from Commercial Club Good Roads Committee to the City Commission,” Cleaning Up the City, January 12, 1914, Chamber History, Salt Lake Chamber of Congress.

“Local and Other Matters,” The Deseret News, April 4, 1883.

Martin V. Melosi, The Sanitary City: Environmental Services in Urban America from Colonial Times to the Present (Pittsburgh: The University of Pittsburgh Press, 2008).

Do you have a question or comment? Write us at “ask a historian” – askahistorian@utah.gov