Salt Lake West Side Stories: Post Sixteen

by Brad Westwood

Throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth century, businesses and government entities targeted Pioneer Park for what they labeled as “public good” purposes. The park, of course, had many identities. It was the site of several public work projects, and it stood as a memorial to Utah’s Mormon (members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) Pioneers.

By the mid-twentieth century, state and city leaders generally viewed Pioneer Park and its surrounding neighborhood as a blighted urban district eligible for large-scale government or private redevelopment ventures. While Utah’s government, business, and civic leaders were in constant discussions about plans to redevelop the neighborhood, new and old immigrants, people of color, and some poor working class white citizens, were working and living out their lives in the neighborhood’s many overlapping micro-communities.

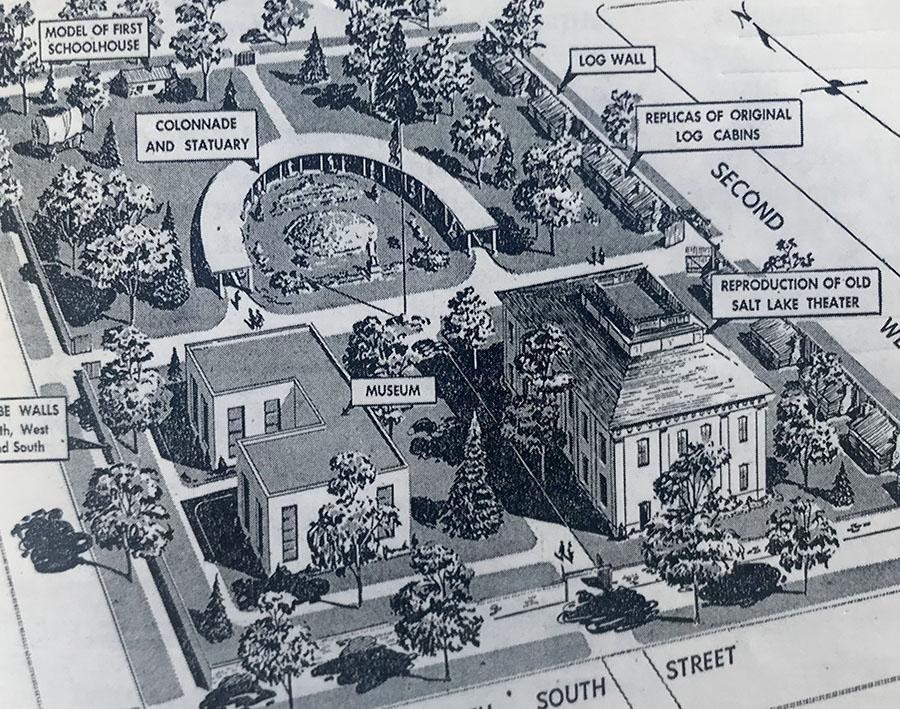

There were two large and respected history groups who worked to preserve the park, even to revamp it into a hub for Utah’s state history. These groups were the Daughters of Utah Pioneers (DUP) and the Sons of Utah Pioneers (SUP), both of whom organized and offered persistent lobbying, or soft power campaigns, to prevent large businesses and state and city organizations from developing the park beyond its 1898 declared use as a memorial to the Mormon pioneers. One well-publicized project proposed to turn the park, and the block east of it, into a large parking garage and civic auditorium. The SUP and DUP resisted such plans however they had their own plans for the park. During the mid-1950s the SUP campaigned, unsuccessfully, to transform the park into a reproduction of the original 1847 pioneer fort. Another plan included constructing a Utah history complex complete with a museum, a reproduction of the Salt Lake Theater (1861-1928), and a replica of the first pioneer schoolhouse, complete with partial fort walls and a group of log cabin replicas. Despite their best efforts, this SUP’s plan to transform the Pioneer Park into an idealized “fort” and museum complex proved unsuccessful.

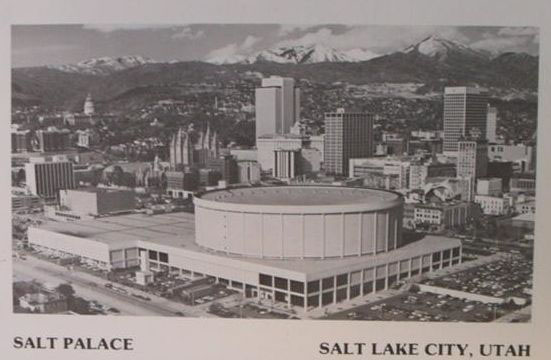

Construction projects dramatically changed the physical and social makeup of Salt Lake’s west side. During the 1960s, planners submitted a proposal to construct the Salt Palace, which was a major undertaking. After five decades of additions and alterations, the Salt Palace complex now stretches from South Temple to 200 South and West Temple to 300 West. The completion of the Salt Palace all but destroyed Salt Lake City’s historical Japan Town. Japan Town was an urban enclave that was once occupied by scores of Japanese-owned stores, clubs and associations, factories, business offices, and two churches, one Buddhist and one Christian. The two religious sanctuaries, and an adjacent Japanese garden, are all that remain of this once vibrant micro-community.

During the 1960s, new construction projects dramatically changed the physical and social makeup of Salt Lake’s west side.

While Utah’s Japanese American population expanded to other parts of Salt Lake City and across the Intermountain West, many still considered Japan Town their community’s heart and historical home. However, as the number of downtown Japanese residents dwindled, business leaders and city developers, throughout the planning and eminent domain process (compulsory government land acquisition), maintained a biased and dismissive attitude concerning the neighborhood’s longstanding cultural importance.

In our next installment of Salt Lake West Side Stories we will analyze the expansion of Interstate-15 and tell the story regarding how Salt Lake City lost all but one pioneer square.

Do you want to read the next post (Post 17)? TWENTIETH AND TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY PIONEER PARK NEIGHBORHOOD DEVELOPMENTS

Click here to return to the complete list of posts.

Contributors: This post was researched and written by Brad Westwood with a whole lot of help from friends. Thanks to our sound engineer and recording engineer Jason T. Powers, and to his supervisor Lisa Nelson, both at the Utah State Library’s Reading for the Blind program. Thanks also to yours truly, David Toranto, for narrating this post.

Selected Readings:

T. Michael Hunter, “A Time for Change: Improving Salt Lake City, 1890-1925,” Pioneer (Fall 2003): 18-24.

Julie Osborne, “From Pioneer Fort to Pioneer Park” Beehive History 22, from Historytogo.com, April 20, 2016.

Do you have a question or comment? Write us at “ask a historian” – [email protected]