Salt Lake West Side Stores: Post Twenty-Four

By Brad Westwood and Cassandra Clark

The above photograph was described by the photographer as “Wright’s Card Club, Blacks, at 313 E. 8th S. [Salt Lake City, Utah], April 27, 1945;” Ray King, photographer; Salt Lake Tribune Negative Collection, courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

This post was updated and expanded in early September 2022 and in February 2023.

With the first African American churches located in this neighborhood, between the city’s railroad facilities, the city’s vibrant African American community had its beginnings.

Besides the known pre-settlement explorers and travelers (see “Blacks in Utah History: Unknown Legacy“), African Americans entered the Salt Lake Valley in the mid-1800s as both enslaved and free individuals. African American settlers were some of the first inhabitants of Mormon settlements dating back to 1847. Later, the arrival of the railroads increased their numbers substantially, especially after the 1880s and into the mid-twentieth century. Many black Utahns were employed in railroad construction and maintenance, with the largest number served as train porters, cooks, and waiters. In 1873, Salt Lake City’s African Americans held a public citizens’ meeting to discuss how to claim and strengthen their rights under the 13th amendment (which technically went into force in early 1865). Beyond the railroad, Salt Lake City’s African Americans worked as miners (some owning mining claims), servants, dressmakers, barbers, and shoemakers.

Salt Lake City had a small but vibrant African American community for most of its history – almost twelve hundred African American Utahns were counted in the Census of 1910. African American Utahns opened hotels, restaurants, and clubs that served Utah’s African American citizens. The majority of African American-owned businesses were located around, and between, the city’s railroad depots near today’s Pioneer Park.

Many previous historical narratives have mistakenly concluded that nineteenth century Utah was a more law-abiding, better organized, less violent, and peaceful place in comparison with the rest of the otherwise lawless and vigilante-prone American West. Recent deep dives into the history of the American West and Utah’s early settlement and territorial periods offer a more nuanced history of the complexity and interconnection of the West with the rest of the United States. What historians have uncovered is that Euro-Americans seeking to colonize the Great Basin participated in violent acts against Native American groups. Additionally, Utah settler history includes cases of domestic violence, inter-ethnic violence, and so-called “mountain justice”; families, individuals, and/or communities also often chose to deal with criminal behaviors outside of the law. What is important to note is that violence was not unique to the western portion of North America, it was truly a nation-wide experience. Concepts of the American west only as “wild” were circulated by media and fiction stories during the late nineteenth century. Thus, the lynching and violent acts towards African Americans and people of color in Utah, which happened in both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, must be understood within both regional and national backgrounds.

One such part of Utah’s complicated past includes the lynching of African American William “Sam Joe” Harvey. Harvey was a United States Army veteran who arrived in Utah in 1883. Previous to this, he lived in Pueblo, Colorado. Likely, Harvey may have come to the city via the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad which opened its service from Colorado to Salt Lake City in May of 1883, with a direct link to Pueblo. According to sources, he established himself as a “bootblack,” or boot shiner, in front of “Hennefer & Heinau’s Barbershop” located on Main Street (known previously as East Temple) between 200 and 300 South in Salt Lake City. On the morning of August 25, 1883, bystanders accused Harvey of shooting and killing Salt Lake City police chief and captain, Andrew H. Burt. In less than thirty minutes after Captain Burt’s death, bystanders beat him, fellow police officers apprehended him and also beat him, and then released him from the jailhouse to an angry mob, who proceeded to lynch him. After his presumed death, his remains were then dragged down State Street, in the vicinity of the Salt Lake Theater.

It is important to recognize that accounts regarding Harvey’s actions on that hot August morning (it had not rained for many weeks prior) come from the perspective of the lynchers who wanted their act to appear justified. Also, it must be made clear here that Burt’s fellow police officers, not the violent vigilante mob, denied Harvey his constitutional right to due process. Harvey was not given the opportunity to testify, nor did a court of law evaluate evidence regarding his alleged killing of Burt. We are largely stranded without a shred of Harvey’s perspective; thus, we can only make assumptions about what happened the day Burt died.

According to newspaper accounts, Harvey entered a main street restaurant owned by Afro-Caribbean American businessman Francis H. Grice (described as a “mulatto,” a miner and businessman who moved to Salt Lake City in 1871) and supposedly asked Grice for a job. Grice offered Harvey two dollars a day and transportation to and from his farm located in Murray. Grice claimed that after he told Harvey about the location of the farm, and the work he might do there for Grice, Harvey allegedly yelled at him and his customers. Grice said Harvey also pushed him outside and pulled a gun out. Harvey then left the restaurant and Grice went to the police station and met with Captain Andrew Burt – a well-known and liked marshal with over twenty years of public service and the Mormon bishop of Salt Lake City’s Twenty-first Ward (northeast corner of Salt Lake City) – where Grice claimed that Harvey had threatened him with a gun.

Burt set off on foot to locate Harvey. He found him on the corner of Main Street and 200 South holding a handgun and rifle. After leaving the restaurant, Harvey apparently entered a nearby general store and bought a 45-70 rifle and two boxes of cartridges. Newspapers alleged that Harvey shot Burt after the officer asked Harvey if he was “an officer.” Burt staggered from the scene and subsequently died in a nearby drug store from his wounds.

Eyewitnesses apprehended Harvey and held him until the police arrived to take him to the county jail that was located adjacent to the county courthouse at 156 West 200 South. Reports claim that officers severely beat Harvey while he was in their custody. The officers thereafter surrendered Harvey to an angry mob of Salt Lakers (some accounts take pains to say the mob included both Mormon and non-Mormon citizens) who had gathered at the courthouse. “Dozens of hands” grabbed Harvey, and minutes later, fashioned a painter’s rope into a noose and hung him from a rafter in a nearby livery stable. The mob then dragged his corpse behind a team of horses down State Street, two blocks south and east of Temple Square, until Salt Lake City Mayor William Jennings stopped the violent, very public, and revengeful act.

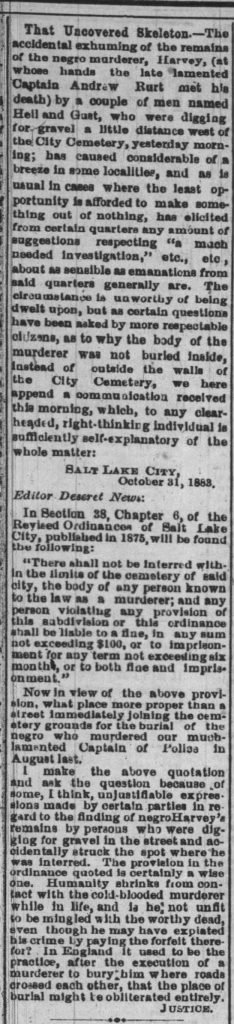

Burt was one of the first members of the Salt Lake City police to be killed in the line of duty. His headstone reads, “He met his death at the hands of a desperado.” Today Burt’s murder is recognized with a street plaque, a plaque that does not mention that Harvey was immediately lynched or that Harvey was an African American citizen. Harvey’s body was buried in a shallow grave just outside the Salt Lake City Cemetery, and his skeletal remains were found accidentally two years later by two men digging for gravel. Harvey’s remains were placed in a gravel and soil borrow pit. Read about the remains being found and the justification for Harvey’s mean burial, in the above newspaper article.

Of course, Burt’s murder was not Salt Lake City’s first nor last. However, most defendants received – more or less – their constitutional right to due process. The act of vigilante justice and its confusing newspaper coverage speaks volumes about race relations in nineteenth century Salt Lake City. Captain Burt’s memorialization, which included a eulogy delivered to a packed house at the Salt Lake City Tabernacle, demonstrates how early Utah residents honored their most respected community members. In contrast, the lynching of Harvey was not atypical of white and African American citizens’ interactions in post-Civil War America. On a national scale, white citizens used the act of mob violence and lynching to enforce and uphold racial and class hierarchies. In short, Utahns chose to honor Burt while simultaneously believing that Harvey, an impoverished African American man, was guilty of murder without public explanation or trial. An official inquest was offered after the lynching, announcing that those who murdered Harvey were unknown. Remembering what mobs had done to Mormons before coming to Utah, Elder George Q. Cannon (1st Presidency, LDS Church) wrote this regarding Harvey’s lynching:

“A dispatch had just been received from Salt Lake City to the effect that Captain Andrew Burt, chief of Police and Marshal of that city, had been shot and almost instantly killed by a negro desperado while endeavoring to arrest him. An infuriated mob had seized the negro and hung him, and his body was afterwards dragged through the streets. I was greatly pained at this news. The death of Captain Burt was a very shocking occurrence; for he has a large family who were dependent upon him for support, and besides he has been a most excellent officer, greatly respected in that capacity, and one of the best Bishops in Salt Lake City, he being Bishop of the 21st Ward. But the hanging of the negro, and the treatment of his corps afterwards, shocked me greatly. I have a deep-rooted and invincible hatred of mobocracy in every form. I cannot justify it…. This negro merited death; but better that a hundred bad men should escape the penalty of the law than that we should trample upon law to execute vengeance upon miscreants like him. These were my feelings upon hearing the dispatch and I spoke very strongly upon the subject.”

See GQC Diaries, Church Historians Press, 22 August 1883.

Without a doubt, this incident had a chilling effect on the approximately 250 African Americans living in the Territory of Utah, including the LDS African American farming community at Millcreek, south of Salt Lake Valley. Utah was not a slave state before the Civil War (although it did have a law allowing for slavery in the territory) and wished to stay above the fray in the national slavery debates. Nevertheless, with this action, it was made abundantly clear that citizens of Salt Lake City in 1883 held the same deep-seated racial biases held throughout most of the United States and could lynch Harvey with impunity.

African Americans, enslaved and free, contributed to Utah’s economic, political, social, and cultural landscape. The city’s African American community was larger and much more established – prior to the turn of the 20th century – than what has been written or the extant physical history suggests. There is much more that needs to be researched and written.

As you can see, Utah has a diverse and complex history. In our next post, we will continue to discuss the African American community, in the next century, in and around the Pioneer Park neighborhood.

Would you like to read the next post (Post 25)? African Americans and Salt Lake’s West Side: Part Two

Click here to return to the complete list of posts.

Related Activities:

Explore the 1619 Project developed by The New York Times Magazine which “aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the United States.”

Listen to this Speak Your Piece podcast episode where host, Brad Westwood, speaks to Dr. Paul Reeve (University of Utah professor of history) about Mormonism’s nineteenth century African American members. Reeve also speaks about his book Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (Oxford University Press, 2015) where he considers Mormons and ideas about whiteness within the broader nineteenth century American society.

Get to know Utah’s Sema Hadithi Foundation: “an American heritage and culture foundation that strives to ‘tell the story’ of African-ancestor history, heritage, and culture by researching, preserving, and disseminating information throughout the community.”

Contributors: Special thanks to Dr. Ronald Coleman (professor emeritus, Ethnic Studies Department, University of Utah), Will Bagley (Western historian) and Dr. Cassandra Clark (Public Historian) for contributing to the content of this post.

This post was researched and written by Brad Westwood and Dr. Cassandra Clark, with a whole lot of help from friends. Thanks to our sound engineer and recording engineer Jason T. Powers, and to his supervisor Lisa Nelson, both at the Utah State Library’s Reading for the Blind program. Thanks also to yours truly, David Toranto, for narrating this post.

Selected Readings:

Racial Lynching in Utah (website), University of Utah professors Paul Reeve and James Tabery, 2022.

Miriam B. Murphy, “African Americans Built Churches,” History Blazer, Utah State Historical Society, July 1996.Thomas G. Alexander and James B. Allen, Mormons & Gentiles: a History of Salt Lake City, Pruett Publications Co., (Boulder: Pruett Pub. Co, 1984), 119-120.

Becoming Utah: African Americans and the Pursuit of Equality, Thrive125, Utah’s 125th (1896-2021) Statehood Anniversary Film Series.

Ronald G. Coleman, “Blacks in Utah History: An Unknown Legacy,” in Helen Z. Papanikolas, ed., The Peoples of Utah (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1976).

“Decrease in Lynching Habit” Salt Lake Tribute, January 16, 1913.

“A History of Blacks in Utah, 1825-1910” Ph.D. Dissertation, (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1976).

Christopher Jones, “Black Internationalism in 19th Century Salt Lake City; or a Haitian-born African American in Utah Reports on the Fourth of July, 1873,” in the Juvenile Instructor, July 4, 2018. This is about Francis H. Grice, who is briefly mentioned above.

Harold Schindler, “A Lynching at Noon,” In Another Time (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 1998), 166-169.

Do you have a question or comment? Write us at “ask a historian” – askahistorian@utah.gov